A reflection on growing up in TriBeCa through a post-Sandy lens.

This post was originally published on Medium.

I pulled the car to a stop.

“I’m just going to get out and take a look.”

I left the car running, my wife in the front seat. I stepped out on the cobblestone street, the cold wind from the river on my face. An Uber SUV sat idling to my left as I crossed Desbrosses street, the only other car with a person in it on the block.

The sidewalk hadn’t changed. At the corner of Desbrosses and Washington streets, the grey paving squares were cracked and worn, with

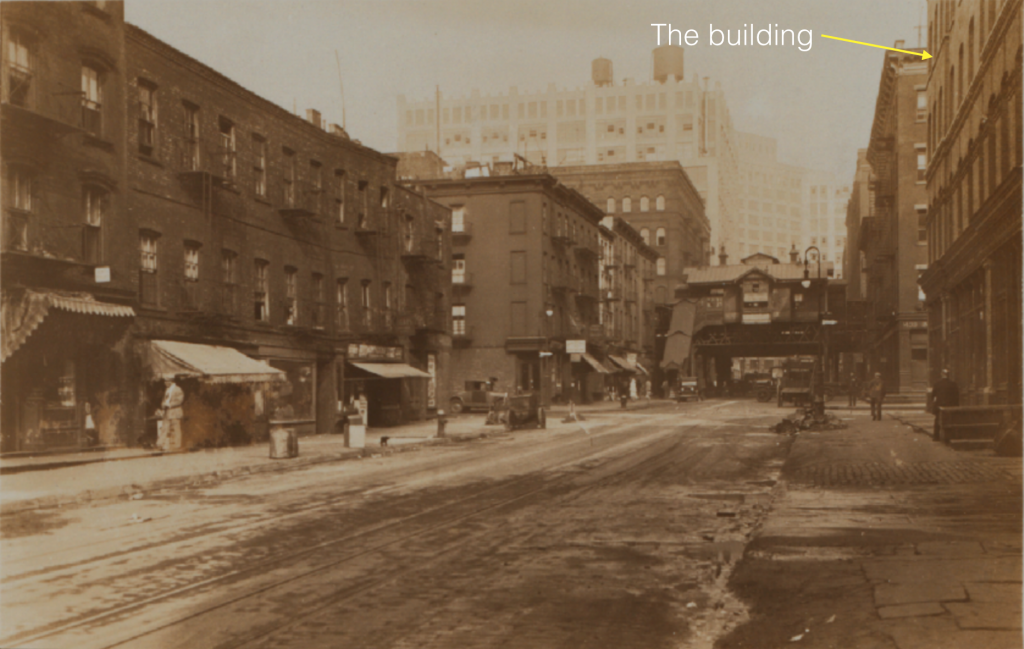

But the building was gone. A green construction fence surrounded the site, with two or three diamond-shaped windows cut in the plywood. Peering through the plexiglass, I saw nothing but a pile of red bricks, patched with snow, filling the bare foundation. I snapped a picture or two, and took a deep breath. The building was gone.

The building was the home I grew up in, on the corner of Desbrosses and Washington Streets, in TriBeCa, lower Manhattan. My parents had lived there all of my life, until Hurricane Sandy pushed the Hudson River four blocks inland, covering the street in three feet of water.

The waters receded, but the chaos left behind by the hurricane eventually culminated in the destruction of my childhood home. The building was gone, my parents were gone (alive, in good health — living elsewhere), and I was left peering through a construction fence at a place that now existed only in memory.

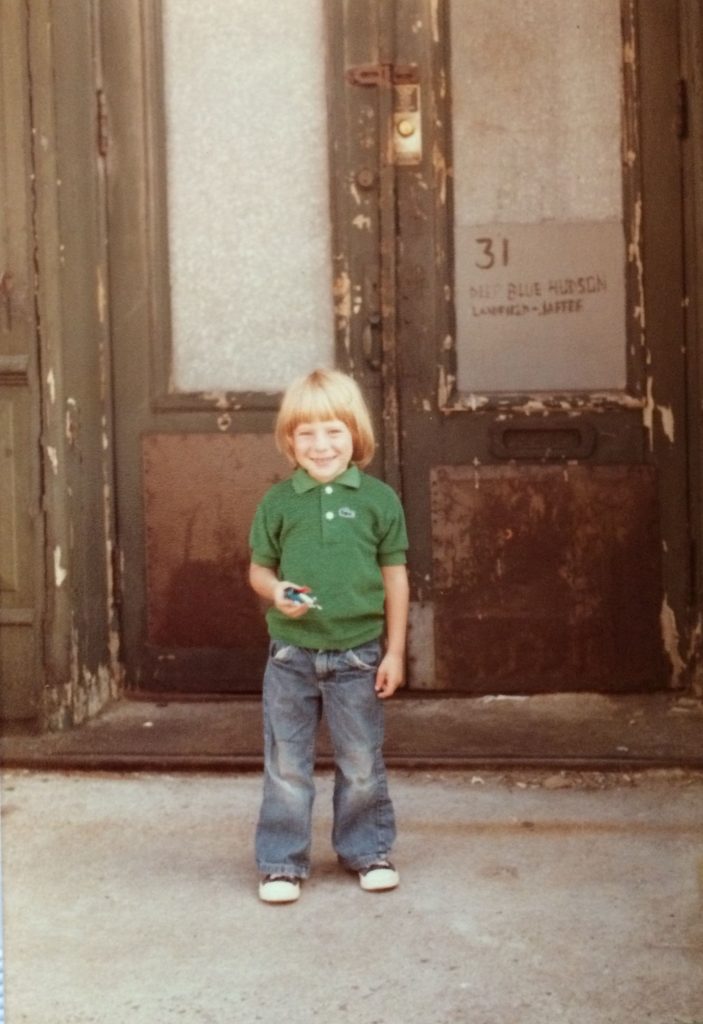

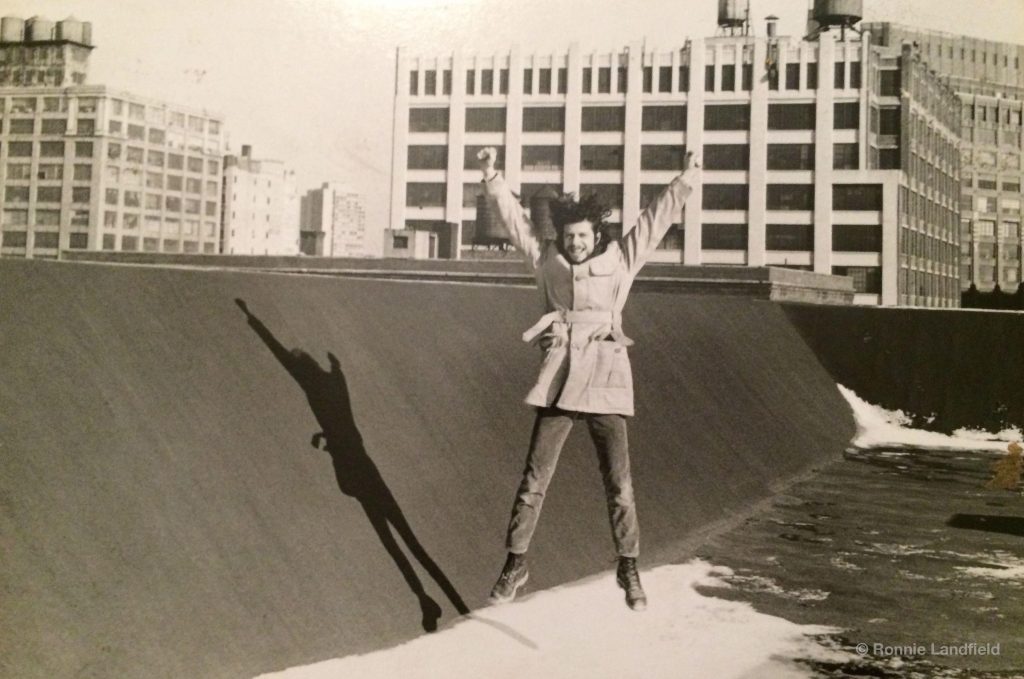

Me.

First, a little bit about me. I was born in 1976, in a hospital called The French and PolyClinic on the west side of Manhattan. The only thing I ever knew about the hospital was that my mother told me it was closed, and that “it was in the theater district.” The French and Polyclinic hospital had been a conglomeration of the French Hospital on 30th street, and the Polyclinic Hospital on 50th street (in the theater district), which joined in 1969, and then went bankrupt and closed in 1977, nine months after I was born (the building still stands on west 50th street near 8th avenue).

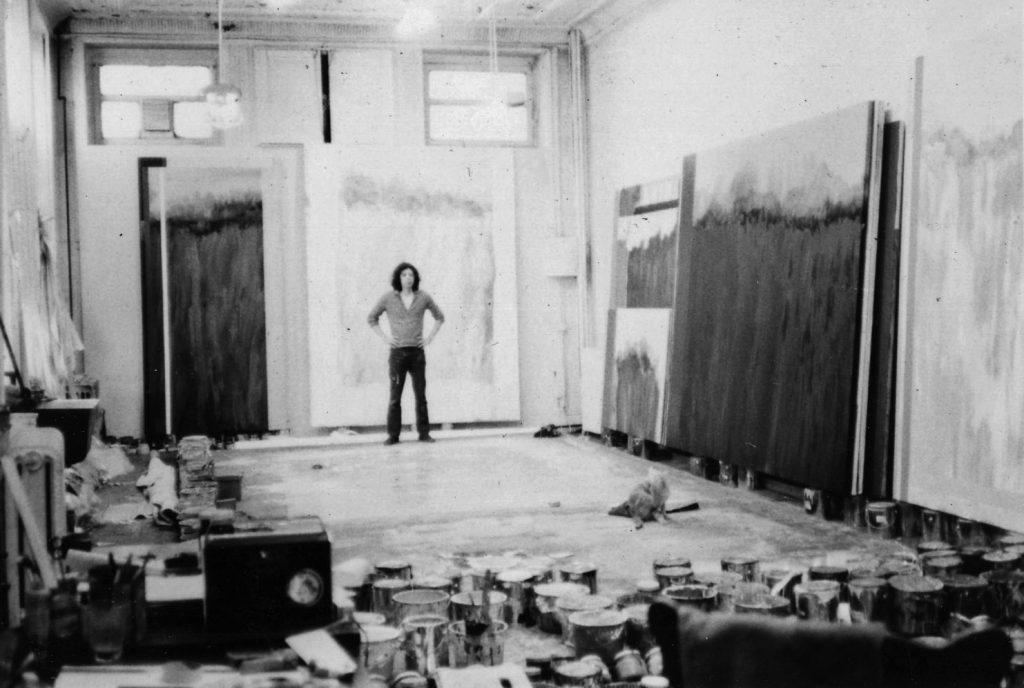

My parents were artists. My father, Ronnie, an abstract painter, had been born and raised in the Bronx, and my mother Jenny, had been born in Manhattan and raised in the East Village and Forest Hills, Queens. They had both been on their own from the age of 16, and like other artists in the 1960s, lived a bohemian life. Seeking space to paint and live, they found their way to 31 Desbrosses street in 1969, after living in a loft at 94 Bowery.

Along with two fellow artists from the David Whitney Gallery — Ken Showell and Bill Pettet — they rented the six-story former Pertussin cough-syrup factory and divided the building between the three artists, each taking two floors.

My father and mother took the first and second floor.

As a child, I knew no other home until I left for college in 1994, at age 18.

Standing there, looking through the hole in the fence, I looked down into the history of the city, an invisible road map of the past. A mirror in which I saw a vision of myself, the chrysalis of a place that could now only be seen with the mind. Staring at the naked foundation, scraped and bare, loaded with crumbled brick, timber and dirt, my mind lifted the stones and the glass, the beams and timbers, the plaster, the tin, and the earth, and reconstructed the place of my birth, the home I lived in but perhaps never knew. I peered through the window and saw the place where my father sat, the table where he made paintings, his desk and his chair.

I saw the staircase, the doors, the floors and the ceiling, the weight of the majestic structure as it sat on the corner of the block like a tall ship against the sky. I saw the history of my life before me, invisible but floating there in the empty space, so close, so solid, so permanent, and yet completely gone forever.

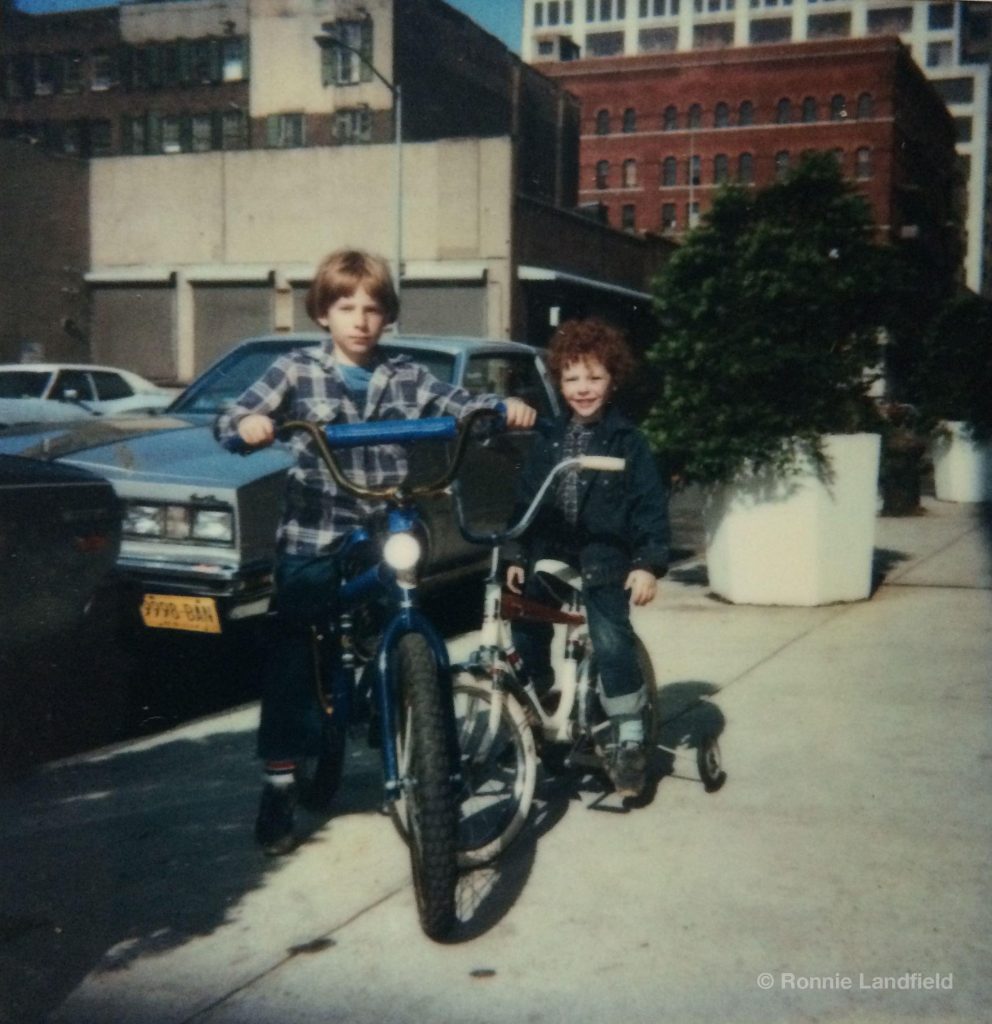

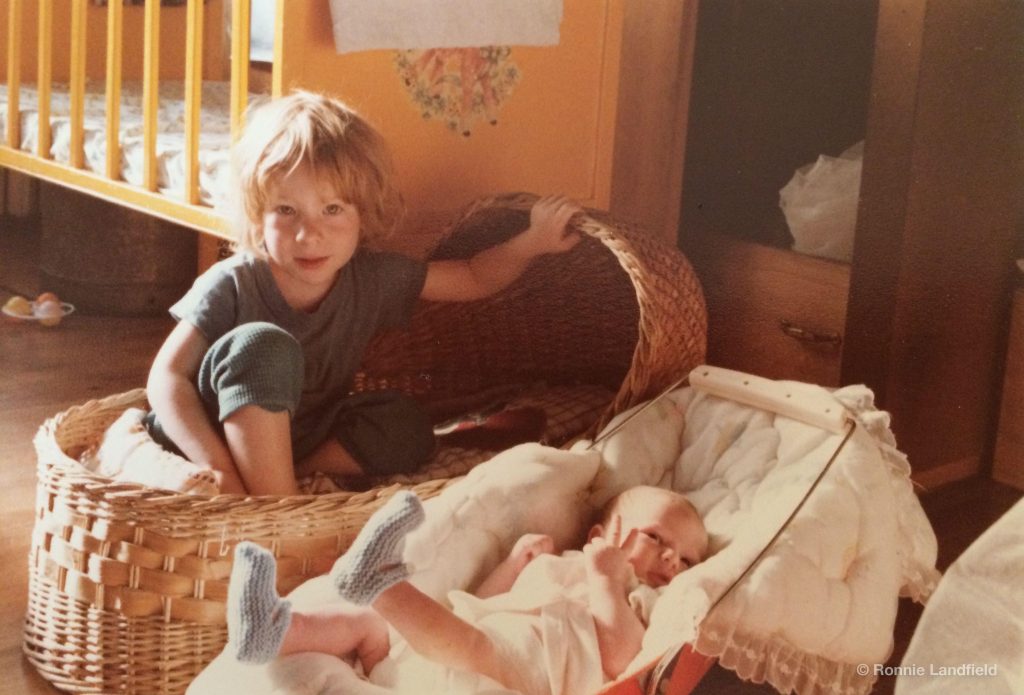

I thought about all the years of growing up, the quiet Saturdays when the neighborhood was even emptier than usual, and my brother and I would ride our bikes on the deserted streets. I saw the room that my brother and I shared, and I remembered my first moments with him, and the shock of suddenly having to share my comfortable world with someone new.

Looking into that void of the empty foundation, it hit me that while those years were gone, no one else would ever share the memory of this place as their home. No doubt something new would be built, but it won’t be the same. When my parents came to Desbrosses Street, no one had lived in the building before them, and now, no one would ever live in it again. And suddenly I wondered, “had anyone ever lived in this place before?”

In wiping the building away, something new emerged: an awareness that there was a “before.” Looking down into the foundation and the surface of the ground it occurred to me, maybe for the first time, that something else had been there before this building, before we were there, and suddenly I wanted to know what it was. I suddenly craved a connection not simply to the place that was lost, but to the land that remained. The physical presence of the building had dominated my experience and my memory, and was seared into my psyche at the level of myth; a place so familiar it extends intact into my dreams. Yet the illusion of permanence had blinded me to something else — the place itself was more than the architecture built on it; it was a part of nature, and maybe had a place in a greater drama than I was aware. Suddenly, I wanted to know, what was this place?

The story of this building, this place, is the story of a new city emerging from the mantle of an old one. But the story of this building is also my story, the story of my family, and a coming of age story for the city and for me.

The story is also about TriBeCa. What it was, how it started, what it is now. And where it’s going.

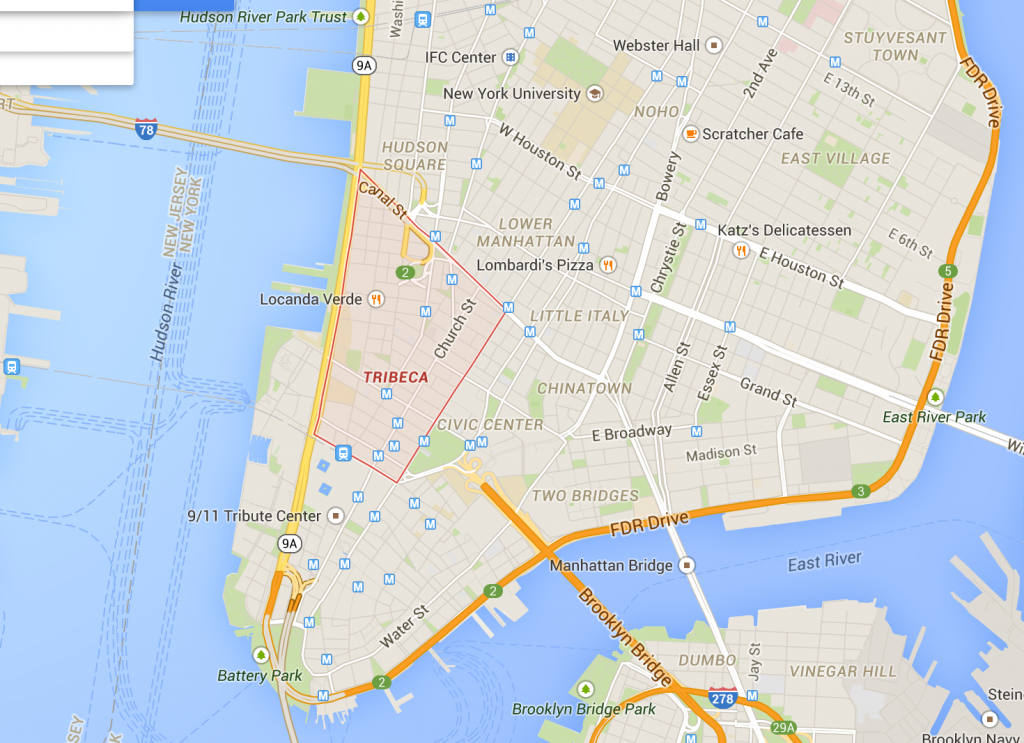

TriBeCa

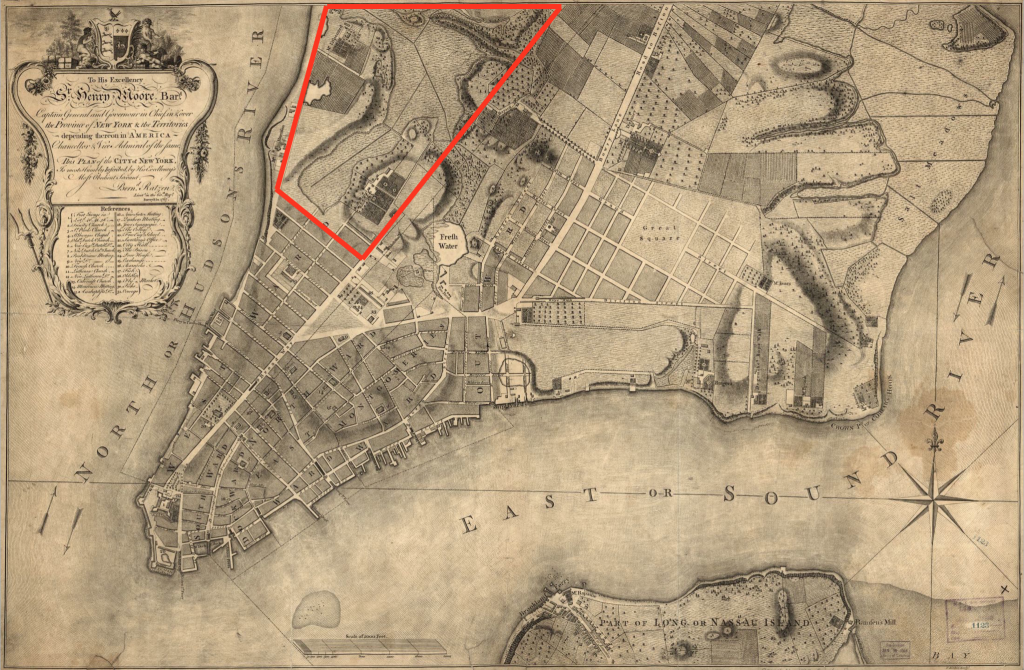

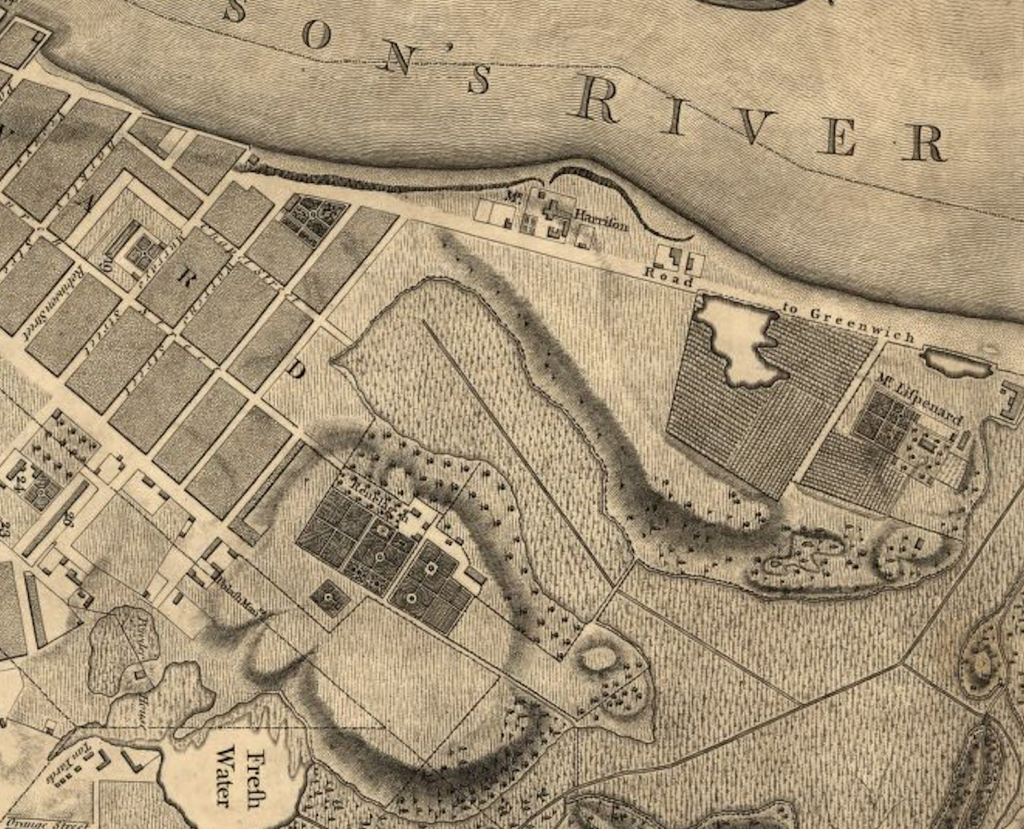

The land that we now call TriBeCa (the Triangle Below Canal, though it’s really a trapezoid) sits on the western edge of the southern shoulder of lower Manhattan, and is formed by the boundaries of Canal Street to the North, Broadway to the east, and Vesey Street to the south (at one time, Chambers Street).

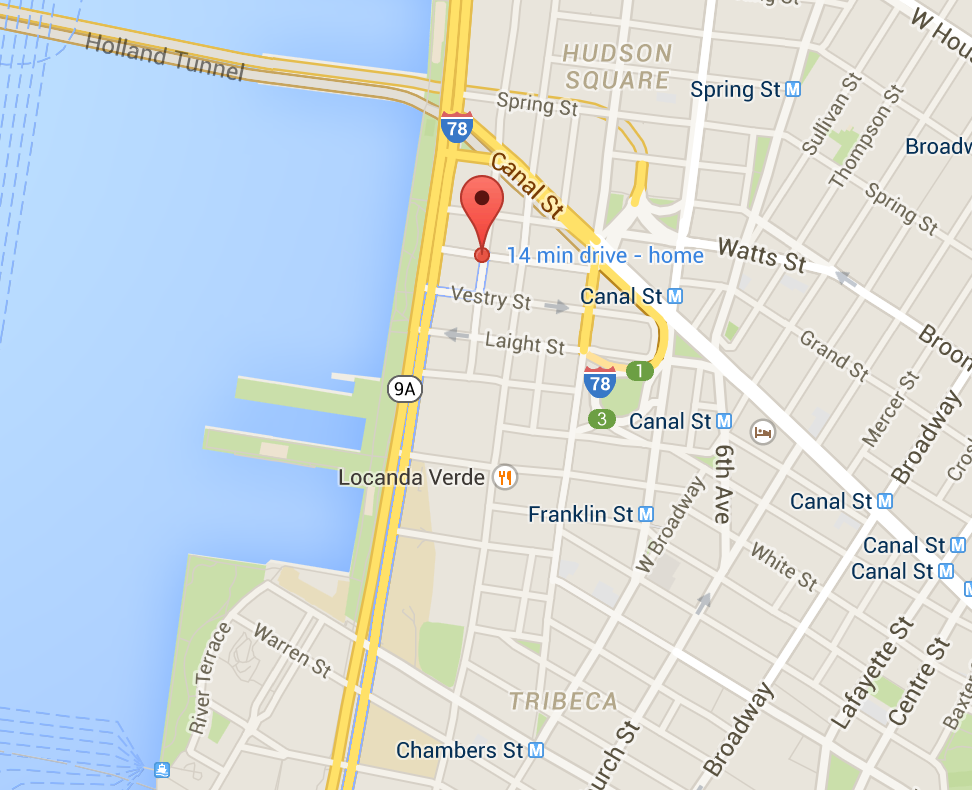

And my home at 31 Desbrosses Street was right at the north western tip, two blocks below Canal Street at the corner of Washington and Desbrosses, one block from the Hudson River.

But how did TriBeCa become Tribeca? Who was Desbrosses? And how did we get there in the first place? To understand that, I had to take a step back and look at a little bit of history.

A Little Bit of History

Formed by the movement of glaciers and rising sea levels at the end of the last ice age, Mannahatta, or “Island of Many Hills,” was inhabited by American Indians for at least 11,000 years. Originally settled by the Lenape, who later sold it to Dutch colonists in the 1600s, Mannahatta was a geographical “goldmine” to a maritime culture. Situated at the mouth of a large estuary, with miles of protected natural harbor and rich with forests, fishing and wildlife, and connected to the pristine wilderness in the north via the Hudson River, settling Mannahatta (later Manhattan) was a colonial “no-brainer.”

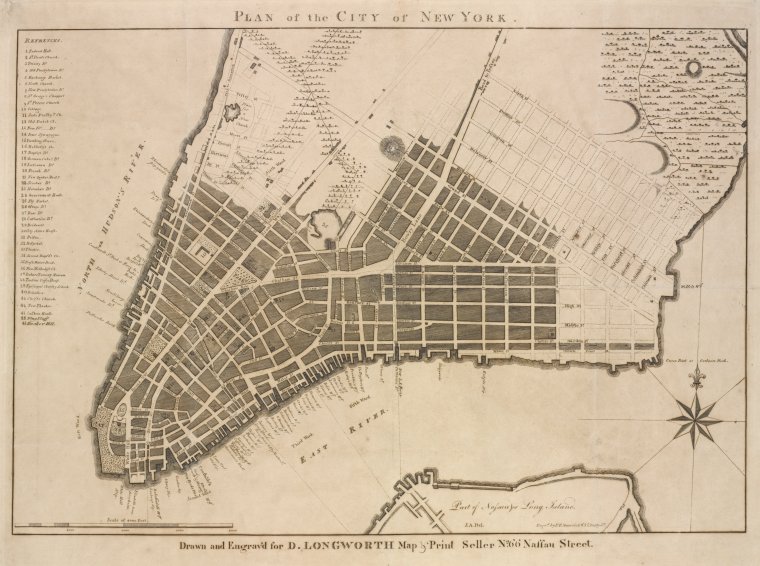

By the middle of the 17th century, the English had seized it from the Dutch, and in 1705, a tract of land stretching from Chambers street to Christopher street (much of what is now TriBeCa, parts of SoHo, and the West Village) was granted to Trinity Church by Queen Anne. This tract of land came to be known as the Trinity Church Farm (Trinity Church still owns much of the land between Canal and Christopher Street, and is one of the city’s largest landholders to this day). In the 18th century, the western shoreline of the island was

As the area was developed it was divided into blocks and lots, and many of the streets were named for prominent vestrymen of Trinity Church, including Chambers, Reade, Duane, Harrison, Jay, Moore, Laight, Desbrosses, Watts, Clarkson, Vandam, King, Morton, and others.

Elias Desbrosses

Desbrosses street itself was named for Elias Desbrosses, a prominent merchant from a French Huguenot family (French Protestants), founder of the New York Chamber of Commerce, and vestryman of Trinity Church who died in 1778 and was buried in the cemetery in the Trinity Churchyard.

Elias Desbrosses was also a warden of the church, and a prominent and venerated member of the congregation, known for his charitable giving.

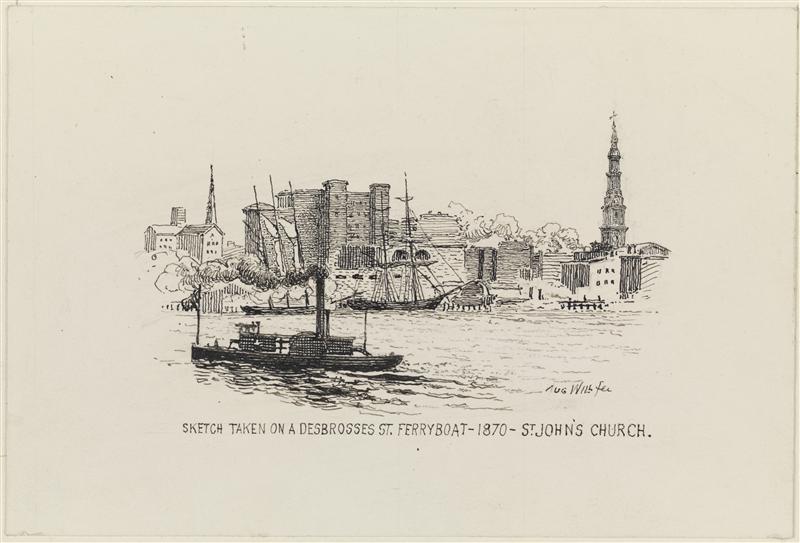

But Elias Desbrosses never lived on Desbrosses Street. The Desbrosses family were merchants involved in the shipping trade, and during their time of the 18th century, virtually all of that business was conducted on the waterfront of the South Street Seaport on the East river. Other than Elias Desbrosses’ affiliation with Trinity Church, his connection with the street that bears his name is virtually nil.

So if Elias Desbrosses didn’t live on Desbrosses Street, then who did?

The answer is Leonard Lispenard.

Lispenard Meadows

Leonard Lispenard was a landowner, merchant, brewer

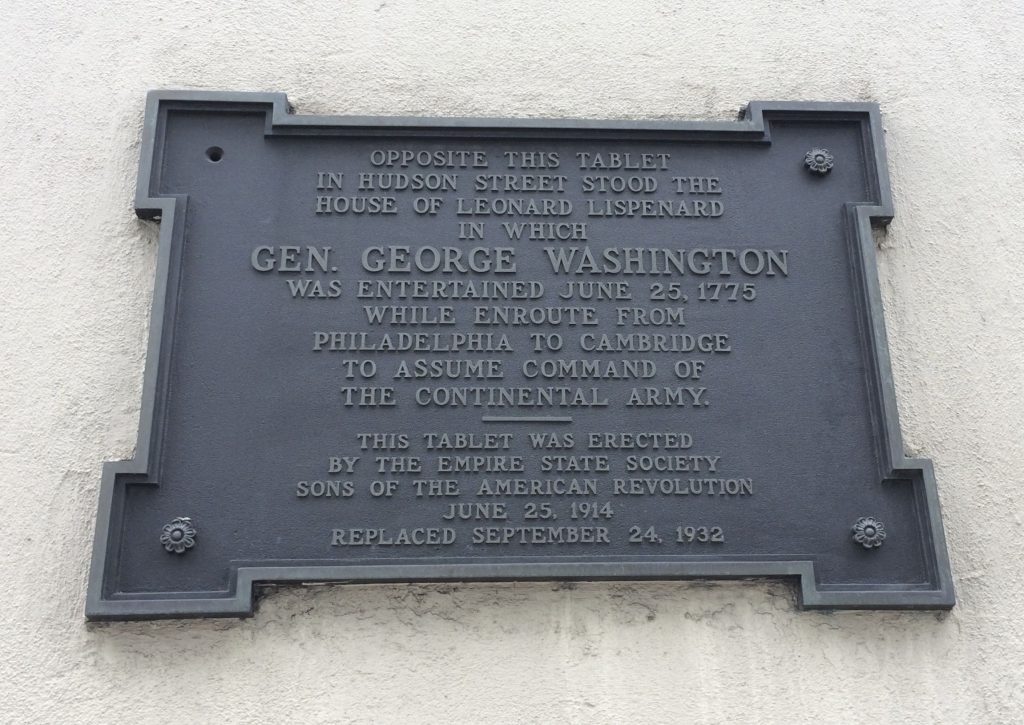

For most of the 18th century, Lispenard’s house was outside the city, and it turns out, strategically located. In 1775, after the battle of Lexington, as George Washington was en route to Cambridge to take command of the Continental Army, he and his men sought a route through New York that would not attract Royalist attention (kind of like

Embarking from Hoboken, Washington crossed the Hudson and landed near what is now Laight and Greenwich Streets. He and his men made their way to Lispenard’s house where they spent the night, thus bypassing the city proper, and the British army.

A plaque at the intersection of Desbrosses and Hudson Streets marks the place where Leonard Lispenard’s house once stood.

So Leonard Lispenard lived at Desbrosses Street, as early as the 1740s.

But that’s still not the whole story.

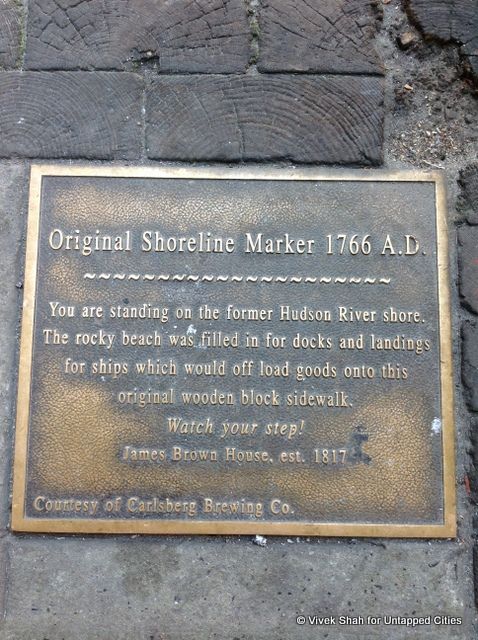

The Lispenard house was located along Hudson Street, on the east side of Greenwich street — on land that was part of the natural shoreline. West of Greenwich street during Lispenard’s time wasn’t land; it was water. The two blocks west of Greenwich weren’t land-filled until at least 1798, and probably not until after 1803 when maps clearly show the layout of the new streets.

So, who lived on the block between Washington and West, along Desbrosses Street?

A Quest Begins

Finding specific answers about places in New York City that are not the sites of major landmarks, or the homes of prominent personages is maddeningly difficult, but being the curious “lay historian” that I am, I turned to every researcher’s secret (and not so secret) superpower: Google. Through Google I found an incredible wealth of documents, books and photographs in the public domain that helped me track the history of the building’s ownership back to around 1911, when a prominent Broadway playwright named Theodore Burt Sayre bought the building as an investment property. But before that the trail went cold. Who built the building? Who owned the land before the building was built? What was there before? These were all questions that I wanted to know, and so off I went to the New York City Department of Records.

The Book of Conveyances

The Department of Records is one of those city agencies that you imagine being something like Gringott’s bank from Harry Potter: a dark, cavernous vault filled with dusty tomes and gnome-like creatures who size you up as though deciding whether to answer your questions or eat you for dinner. And you would not be far off, except for the part about it being dark. Situated on the 13th floor of a building that shares offices with the parole board and a number of other city agencies, the department of records consists of a few desks with some old, out of date computers, a few micro-film review stations, and rows and rows of shelves loaded down with dusty tomes, containing the property records of virtually every city block and plot of land dating all the way back to the 1700s. It was here that I found “The Book of Conveyances” (books, really) that contained the history of the block at Desbrosses and Washington streets, and peeled back the veil of history to peer into the forgotten past of lower Manhattan.

There I found a succession of unfamiliar names, listed in the “Index of Conveyances” (a register of property records) that illuminated New York’s Colonial and post-Colonial past, and the growth of the city into a commercial and financial empire.

Hugh Gaine

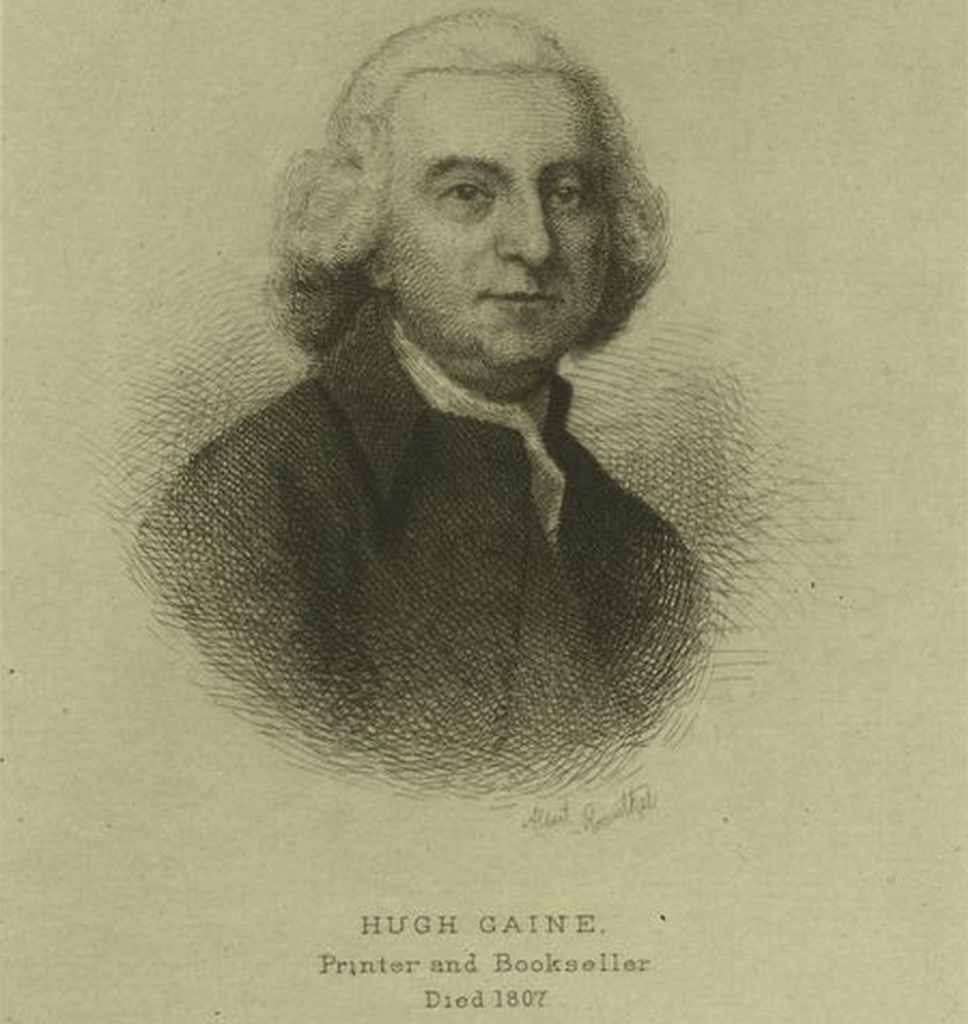

The first of these was a man named Hugh Gaine, who was the first individual owner of the land after purchasing it and several other parcels of waterfront land from Trinity Church in 1803. Hugh Gaine was a prominent publisher during the revolutionary war period (who went back and forth in his loyalties depending on who was in power

Though Hugh Gaine dies in 1807, it’s likely that his heirs, with the aid of a dock builder named Jacob Halsey, began to fill in the land and develop the blocks west of Greenwich street into valuable waterfront property, and by 1824, this task was completed. After the Erie Canal opened in 1825, the Hudson River wharf, with its deep-water berths and proximity to the Washington Market, became a lynchpin of trade between the Port of New York and the interior of the continent, enabling the city to become the largest and most important port of trade in the world. Years after Hugh Gaine’s death, his heirs sell off his holdings, and an 1824 auction notice from his estate lists the block between Desbrosses and Vestry streets, west of Washington Street, as one of the lots for sale.

The Lorrillards & Cammanns

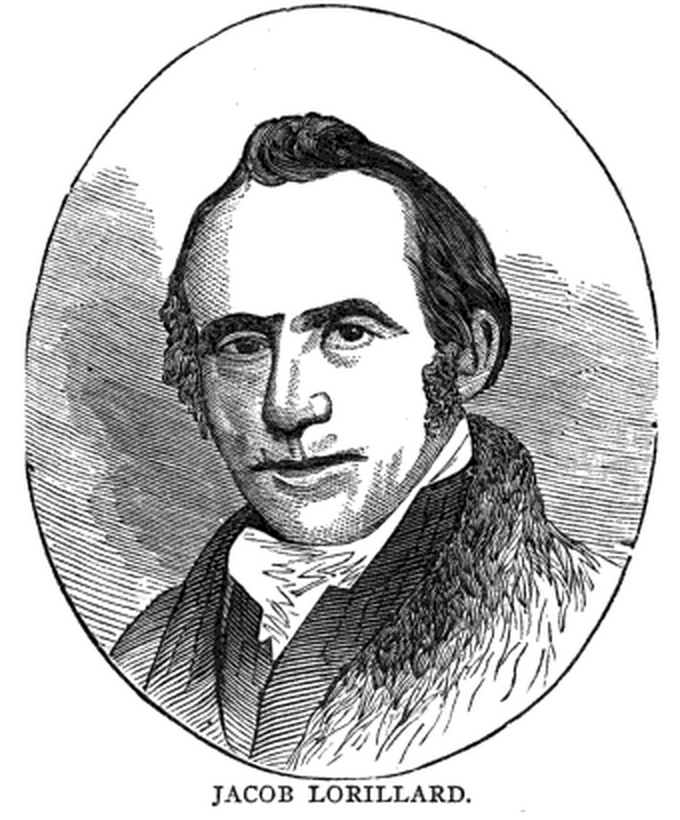

The man who buys the land from Hugh Gaine’s estate is Jacob Lorillard, of the Lorillard family, a prominent family in New York society in the 19th century. While the Lorillard family is known for founding the Lorillard Tobacco Company (later the American Tobacco Company), Jacob Lorillard was a leather tanner, banker, philanthropist and major land speculator (he bought more than 100 lots of property all over lower Manhattan), and he too was a Vestryman of Trinity Church, serving from 1826–1838.

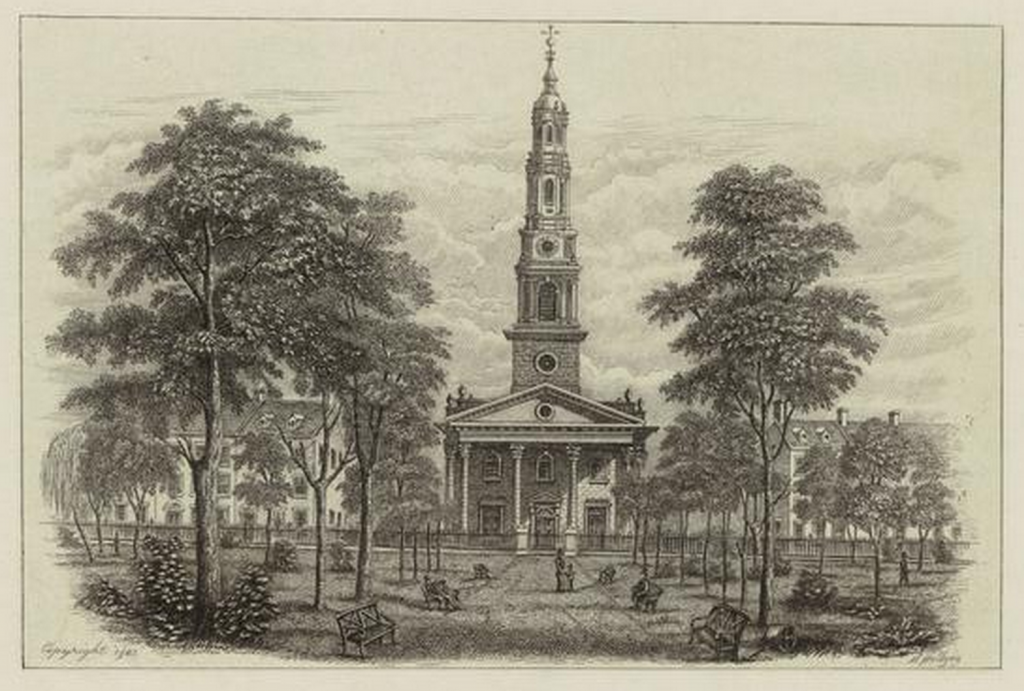

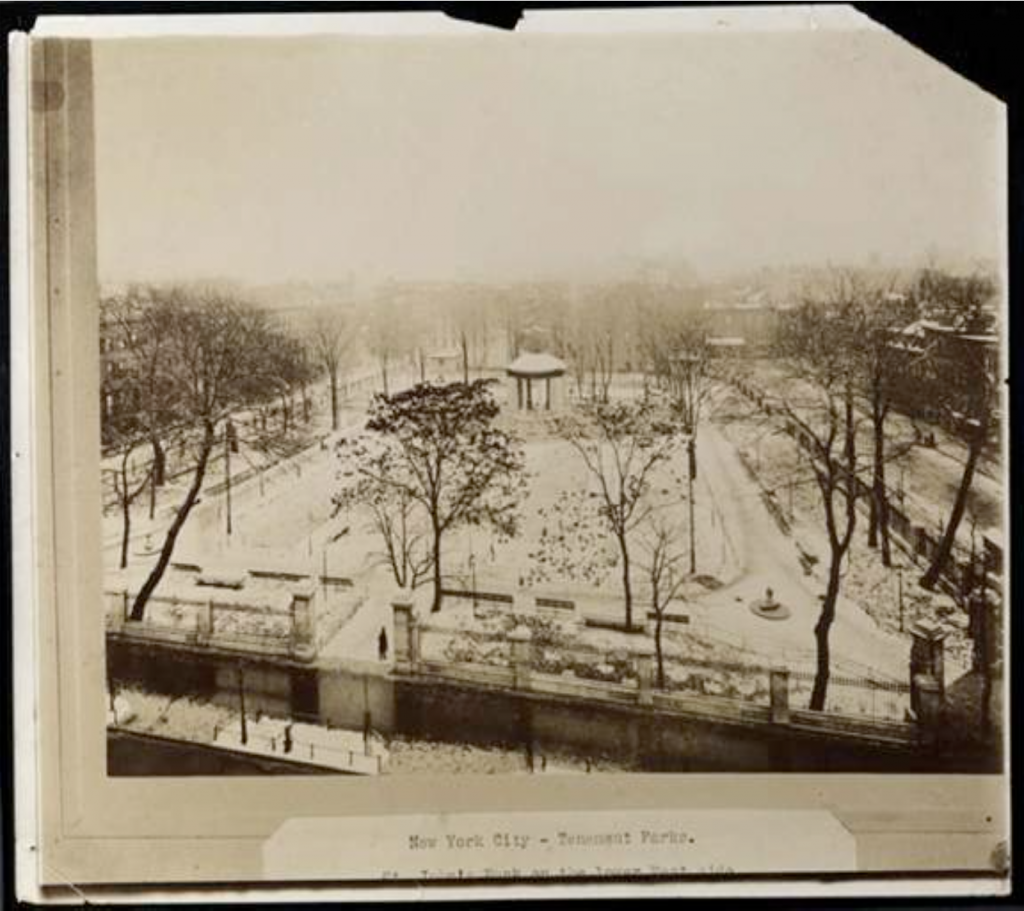

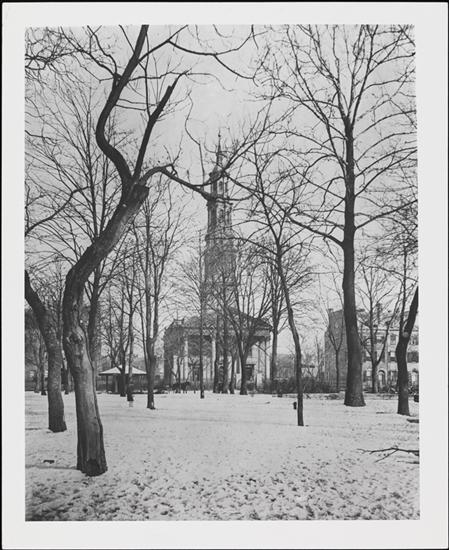

Jacob Lorillard had a house in the Fifth Ward (the area we now call TriBeCa) known as the Lorillard Homestead, at the corner of Laight and Hudson Streets, opposite St. John’s Park (or Hudson Square, now the exit plaza for the Holland Tunnel).

In 1846, after Jacob Lorillard’s wife Margaretta passes away (Lorillard himself dies in 1838), their holdings are divided between their son and five daughters (and their husbands, as women were only just beginning to be allowed to legally own property). Lorillard’s eldest daughter, Catherine Anna, married to a prominent doctor named George Phillip Cammann (one of the inventors of the binaural stethoscope), retains ownership of the part of the block on which 31 Desbrosses Street would later be built. Catherine and George P Cammann live in the neighborhood at the Lorillard Homestead until the 1850s when they move uptown, but the land on Desbrosses Street remains in their hands and in the hands of the trustees of the Lorillard estate until the 1890s.

St. John’s Park

St. John’s Park, and the chapel for which it was named, was built by Trinity Church in

Port of the World

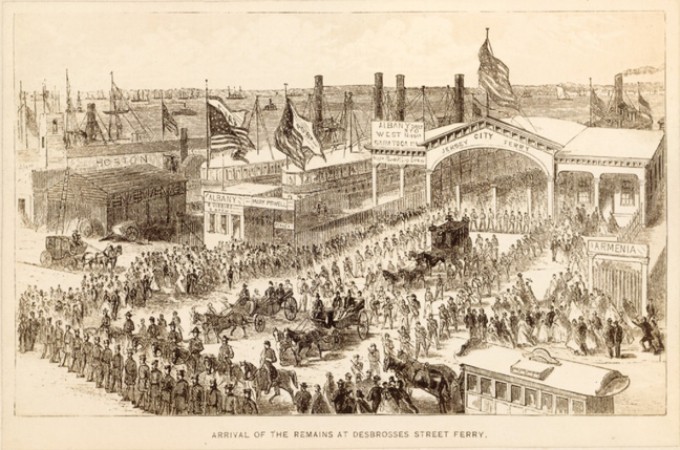

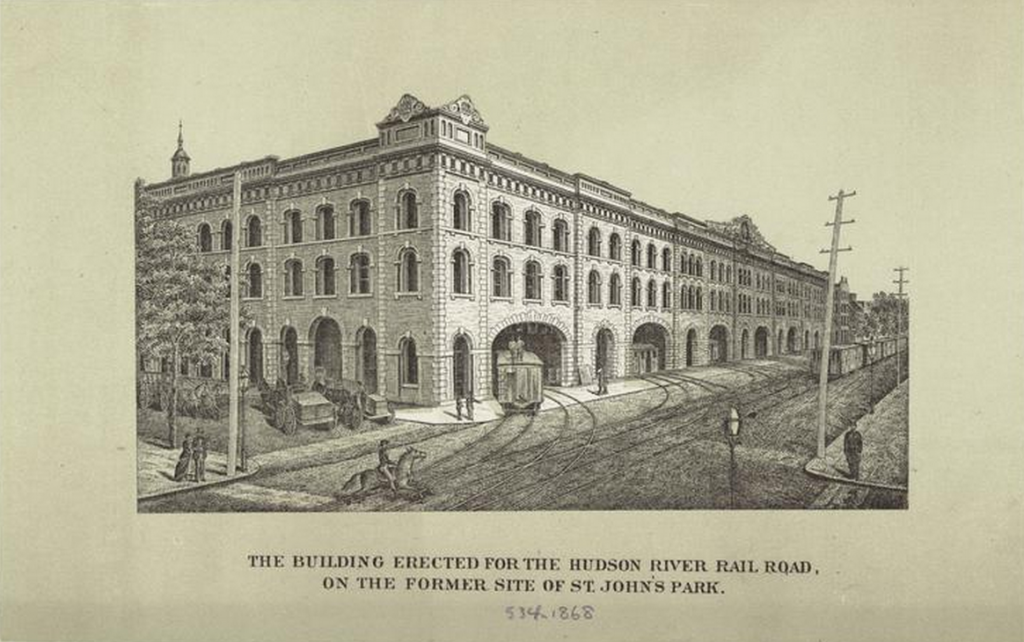

This time period is one of tremendous economic growth in lower Manhattan, including the expansion of the port from the East River, north along the Hudson (also called the North River). In 1862 the Desbrosses Street Ferry opens, and regular crossing to Jersey City becomes routine. The Pennsylvania Railroad opens a terminal at Desbrosses Street, to ferry goods and people back and forth from Manhattan to New Jersey at high volume.

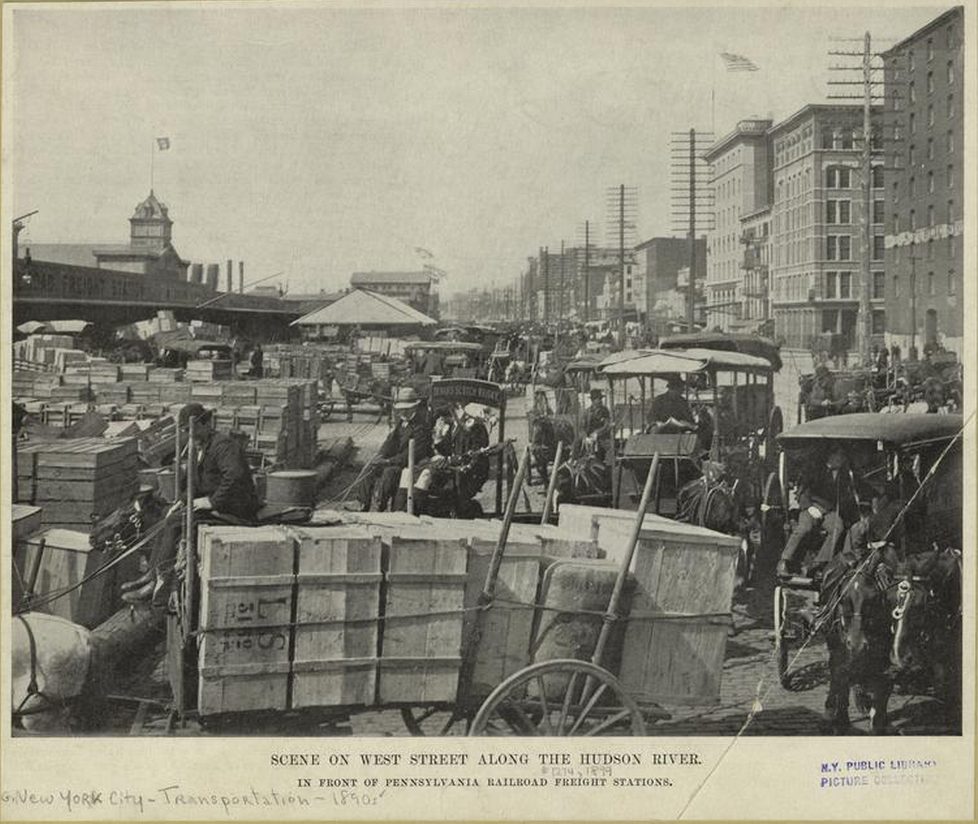

After the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, and the development of newer and larger ships that required deep-water berths, the Hudson River piers formed the foundation of New York’s rise to become the foremost capital of global trade in the world. With a large natural harbor and a water-link to Lake Erie — and by extension, the interior of the North American Continent — New York City becomes the nexus of major industry and trade connecting American goods, capital and resources to the rest of the continental US and the world.

And it is in this environment that the first tenants of 31 Desbrosses Street appear.

Mahogany: John and Francis Copcutt

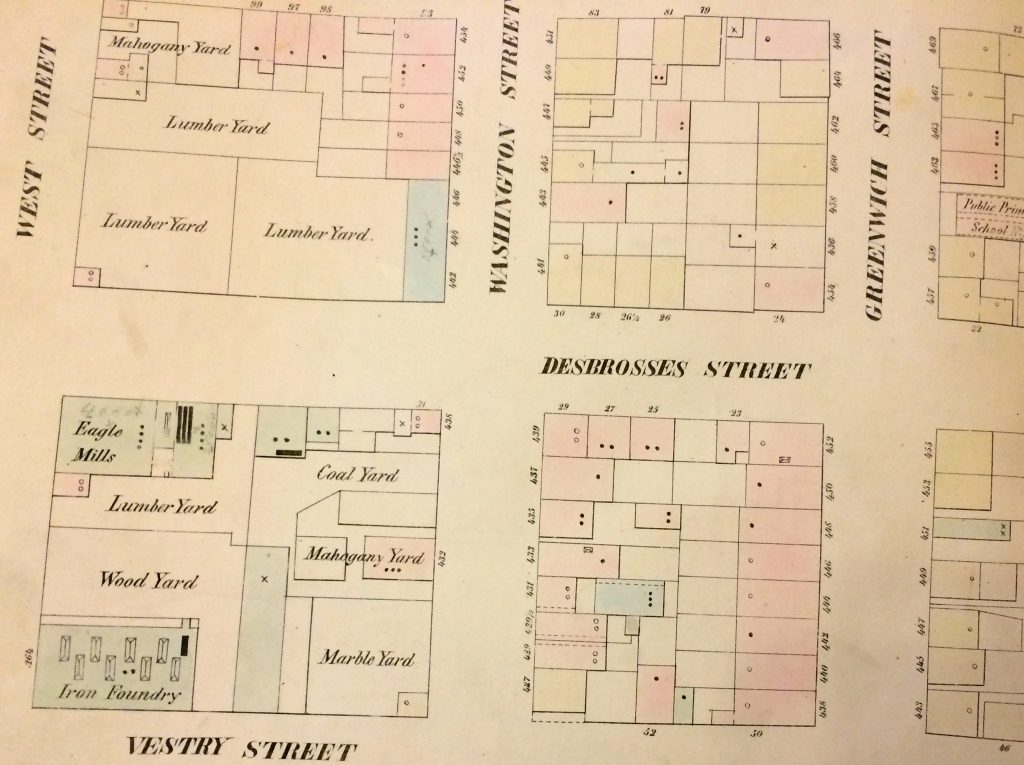

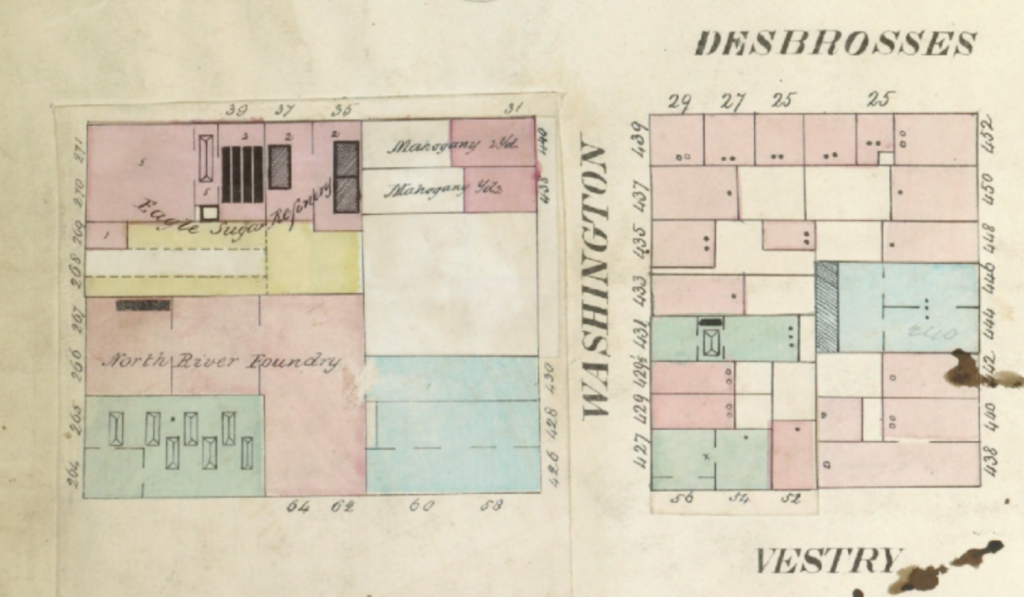

According to William Perris’s insurance maps of Manhattan, by 1853 (and probably before) the corner at Desbrosses and Washington Street was occupied on both sides by storage yards, and the one at 31 Desbrosses street contained coal, and later, mahogany. This lumberyard was owned and operated by two brothers, John

The Fifth Ward

While parts of the Fifth Ward like St. John’s Park were fashionable from the 1820s to around 1850, once rail-lines were introduced to the area, most of the district was taken over by warehouses and manufacturing buildings for the busy waterfront along the Hudson River. Driven by technical advances like the coal-powered steam engine, and later the railroad, the neighborhood lost favor with elites by 1867, when a major rail depot was constructed at St. John’s Park.

The Fifth Ward also constituted

A Building is Born

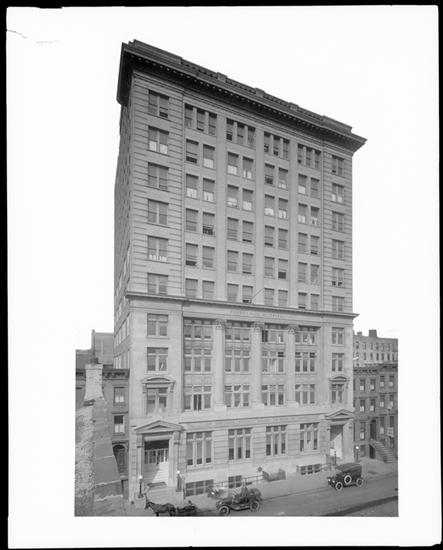

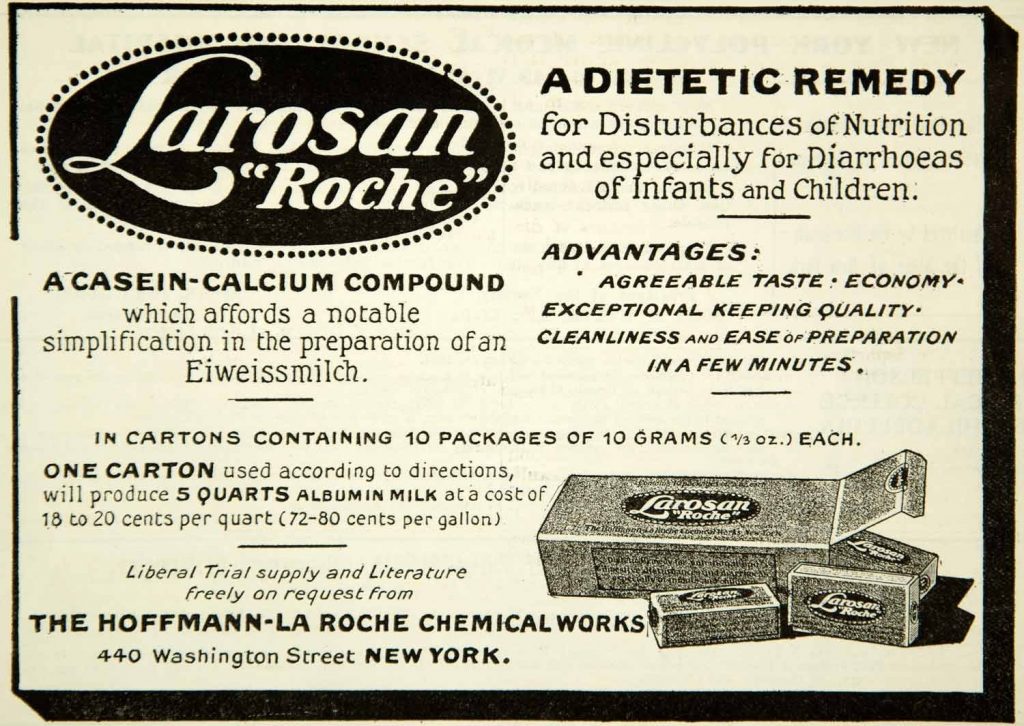

Through the mid-to-late 19th century the property at 31 Desbrosses Street (or 440 Washington Street) changed hands several times, until around 1898, the property comes into the hands of Henry and Hyman Sonn, also known as the Sonn Brothers. The Sonn brothers were Whiskey wholesalers, and in 1899 the “six-story with basement” industrial building at 440 Washington Street is constructed, and becomes their base of operations (the building is technically owned and built by a man named Sylvester L Mitchell and designed by the architecture firm of Kurzer and Rohl, but Mitchell appears to default on the mortgage, and the building is then acquired at auction for $50,000 by the

After the

In 1920 Sayre sells it to the Katzenbach & Bullock Co., also a chemical manufacturer.

Seeck & Kade remain owners of the building until Seeck & Kade itself is acquired by Chesebrough-Pond’s in 1956, a large chemical holding conglomerate. Chesebrough-Pond’s is the last major manufacturing company to own the building at 31 Desbrosses Street. In 1967, the building is turned over to a trucking company, it’s

The Washington Market

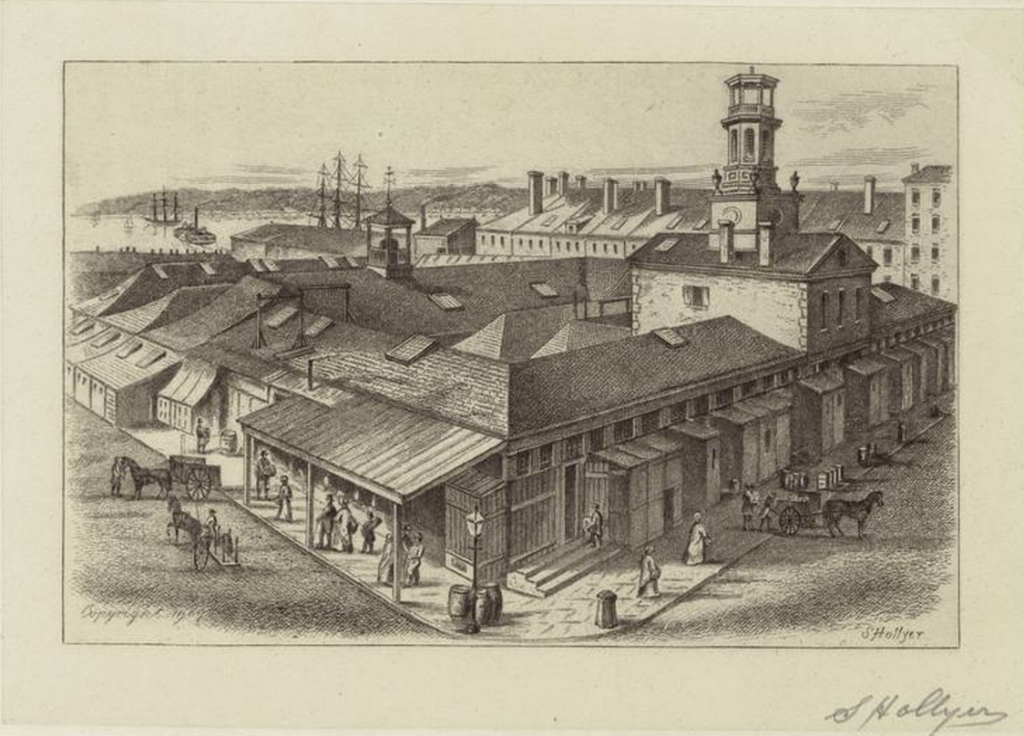

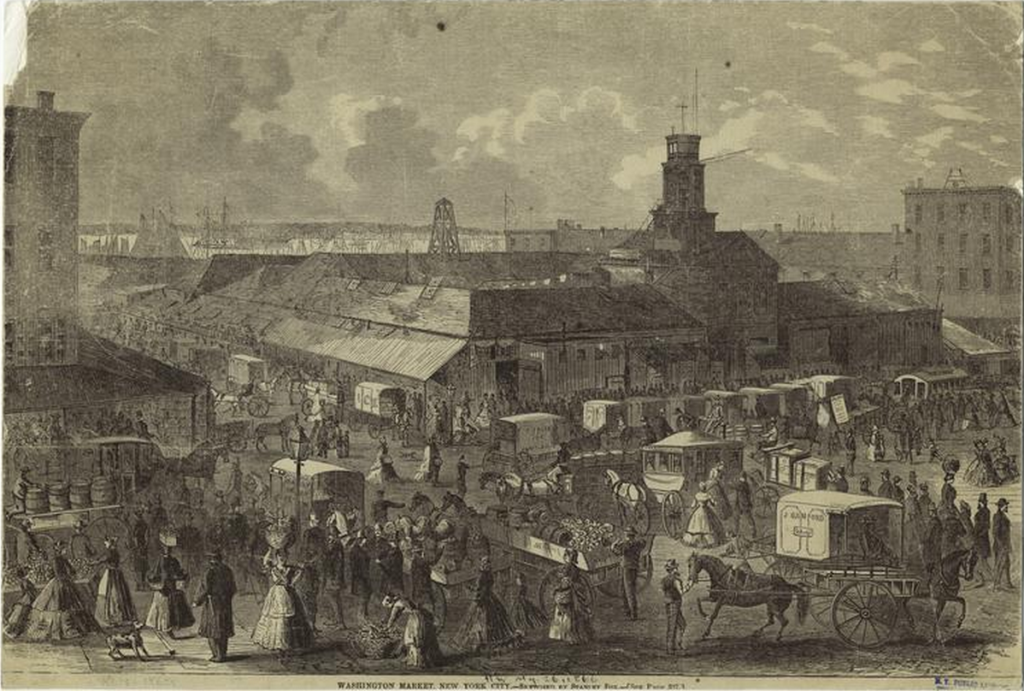

During the 19th century and into the early 20th, the Fifth Ward was a busy mercantile district, driven by the shipping industry and the many docks and shipping berths lining the Hudson waterfront. Goods and materials brought in by ship or manufactured in the city would be transported by barge to and from the West street piers and the Washington Market to rail terminals on the New Jersey side of the Hudson. Several warehouses, some dating from before the Civil War, still line the blocks between West and Greenwich streets, from Hubert street north to Canal.

The Washington Market, a predecessor of the Fulton Fish and Hunts Point markets, was the “Ur” marketplace of wholesale commerce in the 19th and early 20th century, and was the crown jewel and hub of the west side waterfront. Originating as an open-air bazaar in 1812, and centered around Fulton and Washington Streets, the Washington Market was at one point the largest produce market in the United States.

Much of TriBeCa during this time was the receiving point for most of the food consumed in Manhattan, and was nicknamed “The Farm” in part as reference to the sheer volume of farm produce passing through the rail corridors, warehouses, trucking depots and shipping berths along the west side and traded in the Washington Market and its environs.

Post-war Decline

The Washington Market was closed and demolished in 1967 to make way for the World Trade Center. The Freedom Tower currently occupies the site.

The waterfront began its long decline in parallel with New York City’s mid-twentieth century struggles. After World War II, New York had supplanted Paris and London as the financial and cultural capital of the world, yet economic and social forces beginning in the post-war years set the stage for the city’s gradual decline. In 1948, the Interstate Commerce Commission permitted fees to be charged by the barges transporting goods from New Jersey to the piers on the Manhattan waterfront. These fees increased the costs of transporting goods to and from the city, and prompted the decline of the ports and piers, and places like the Washington Market, as the shipping industry sought less expensive means of wholesale transportation. Technology too had a hand in the inevitable end of wholesale shipping in and out of the port of New York: the development of the container ship.

Container vessels, first converted from tanker ships after World War II and later expressly built for the purpose of shipping, enabled bulk loading and moving of cargo at a scale and speed previously unknown in the shipping trade. The new bulk shipping containers could be loaded and secured before arriving at dockside, yet their large size, and the large size of the ships required to carry them resulted in the industry moving to the port of New Jersey at Elizabeth, where there was more space to berth and load the ships. Thus, the confluence of changing technology and modernization of large scale manufacturing and transportation resulted in the virtually complete abandonment of the west side of Manhattan as an industrial center by 1967.

Urban Renewal

The population of New York City also peaked in 1950 and began to decline, as more and more people left the city in the post-war years for newly developed suburbs in the surrounding areas. The population of New York City would not return to its 1950 level again until the year 2000, with the city’s population nadir in the 1980s coinciding with the city’s economic and social woes (and ironically, the growth of its cultural renaissance).

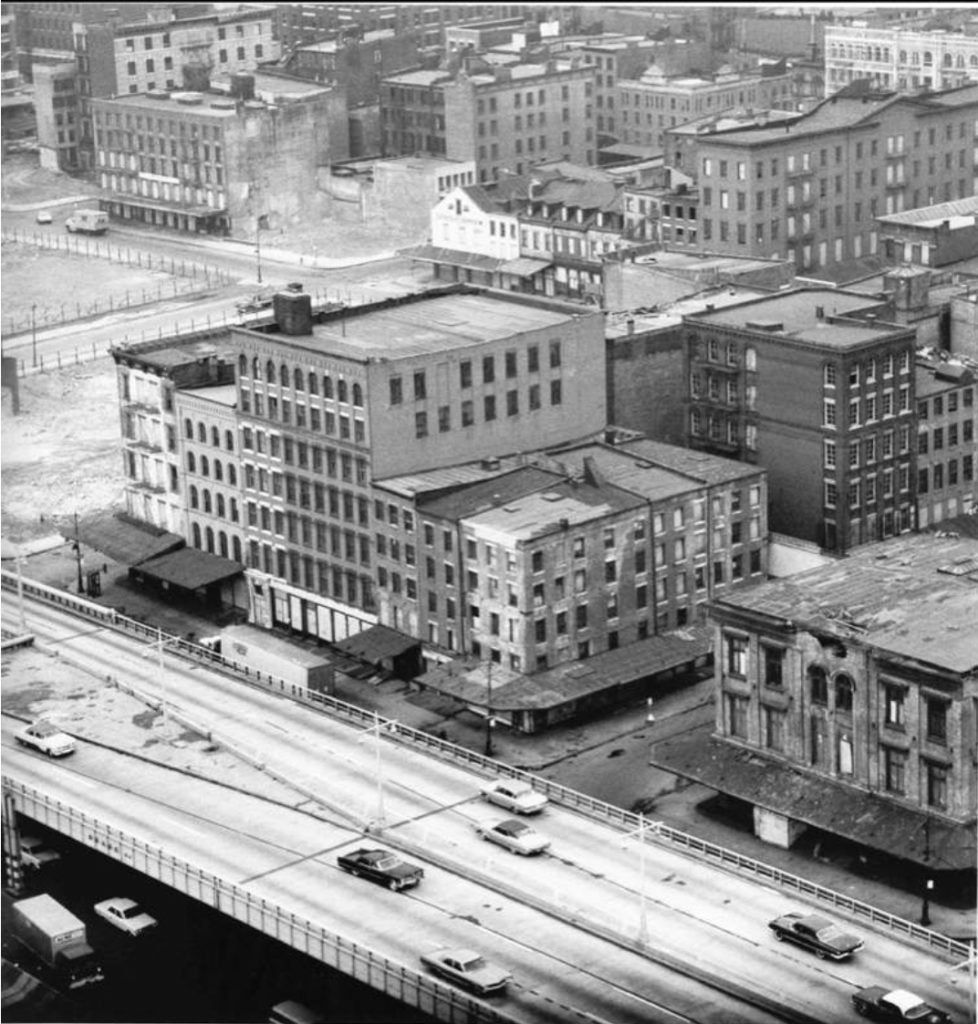

With the decline of the city’s historical manufacturing and industrial base, a declining population and economy, and increasing crime and social unrest in the 1960s, the section of Manhattan from Broadway to the Hudson River and bounded by Reade Street in the south to 8th street in the north became known as Hell’s Hundred Acres. Consisting predominantly of warehouses and industrial buildings, the area was notorious for fires, and though some light industrial activity continued and a few sweatshops remained open during the day, at night the entire area was largely deserted.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a number of urban renewal projects began that transformed the lower west side, including the construction of the World Trade Center, Independence Plaza, the Borough of Manhattan Community College, and later, the Shearson Lehman/American Express complex and Battery Park City. Most of the derelict piers were removed, as well as the majority of the 19th-century era masonry buildings south of Canal street along the river between West and Greenwich Streets.

Enter the Artists

It was into this environment that artists of 1960s New York entered, attracted by the remaining large, industrial spaces with high ceilings and good light, left vacant by the manufacturers who had moved on to greener pastures in New Jersey or the outer boroughs. Because demand for space was lacking and the economy of the city was languishing, rents were low and little attention was paid to artists who began to live in the same spaces where they worked. Because the buildings occupied by artists were not zoned or designed for residential use, the city eventually had to create a legal framework to accommodate artist residents, and amendments were made to zoning laws to create live/work districting to permit visual artists to remain in their lofts. Later, the Loft Law of 1982 would attempt to provide rent protection and greater stability for loft dwellers who were often faced with substandard conditions, eviction, and unfair rent increases.

And it was into this world that my parents found their way to 31 Desbrosses street in the fall of 1969.

Uncovering the details of this narrative revealed a number of things to me. The first was that my parents and fellow artists Ken Showell and Bill Pettet were the first people ever to live on the southwest corner of Desbrosses and Washington streets. What once was water, then a storage yard, and later a manufacturing building that had never housed people suddenly became a place where my father and mother made their home. While the neighborhood had once been a working-class neighborhood for the city’s many Irish and German immigrants, with schools and churches tucked in-between the busy warehouses, those days were long gone. Now, the building at 31 Desbrosses Street stood surrounded by predominantly empty trucking depots and post-industrial derelict warehouses, looming eerily silent on the empty streets. Living at a distance from the populous part of the city defined my parents’ outlook, and would shape my early life and perspective on the city.

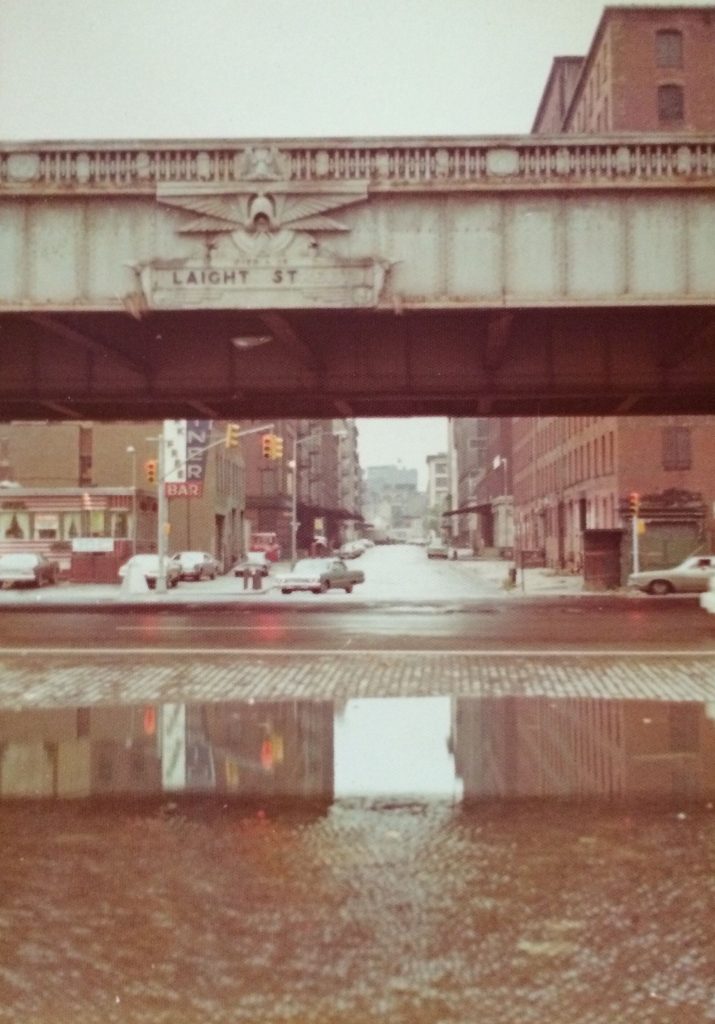

Surrounded on all sides by the ceaseless traffic of the Holland Tunnel along Laight Street in the south, Hudson Street to the east, Canal Street to the north, and West Street and the river to the west, a kind of “hidden valley” was formed in the north of TriBeCa, cut-off from the rest of the neighborhood by the eddies and flows of constant motor traffic. With few residences, services, and very few retail businesses in the area, foot traffic was limited and TriBeCa North was slow to develop.

In my early childhood at the end of the 1970s, there were only a handful of families who lived within a five-block radius of our house, and not many more in the surrounding area.

I have many memories of riding my big-wheel on the derelict off-ramp of the West Side Highway, and of walking almost a mile with my mom to the corner of Bleecker Street and 6th Avenue to go grocery shopping at the Pioneer Supermarket, the only place to buy food for miles. The opening of the Food Emporium on Greenwich Street in the early 1980s was a huge development in our household (though it was still a half-mile away).

My parents would also be among the last people ever to live in the building at 31 Desbrosses Street, as they remained tenants there from 1969 until 2013 when the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy rendered the building inaccessible. They were also the only family to occupy the building continuously for that time period, as the other original tenants moved out and new families moved in.

The Bridge

In many ways, our lives in that building and in the neighborhood of North TriBeCa formed a bridge between the city of the past, with its vibrant industrial and working-class culture — a city of workers, builders, artisans and makers — and the city of today, with its genteel atmosphere, upscale residences, and wealthy inhabitants. And my parents’ lifestyle, living on the second floor of a building fitted for commercial use, with my father’s painting studio on the floor below, while unorthodox, also oddly reflected the customs of artisans of the distant past, when craftsmen of the 18th century lived above the workshops where they plied their trade.

The end product in my father’s case was art, a luxury good

Raising a family in this environment also created its own incongruities. Children need schooling, and by the late 1970s, Ronni Moskowitz had started the Washington Market Montessori School, and PS 3 Annex, which would become PS 234, occupied a small three-story building within the Independence Plaza Complex (now occupied by PS 150), led by pioneering principal Blossom Gelernter. My brother and I, and virtually every other child of artists we knew in the neighborhood (and some from other neighborhoods) became students there. The small school, where there were no desks and the teachers were called by their first names, became the center of our community, and as we grew we watched as the neighborhood grew around it. Washington Market Park, down the block from the school, underwent a transformation from a spartan sand-lot with a jungle gym or

The rapid transformation of lower Manhattan going on around us felt at times like a Bugs Bunny cartoon, the one where the cartoonist’s gigantic hand appears in the frame holding a pencil, and in a flurry of “meta” storytelling, sketches in the scene surrounding Bugs as the action unfolds, sometimes one step ahead of Bugs, sometimes just a few steps behind. So too do the changes taking place now feel like the same cartoon, this time where the cartoonist has flipped the pencil, and erases the scene around Bugs Bunny, leaving him in an unfamiliar and unsettling blank void.

The changes that were taking place in the neighborhood and the city around us ran like seams through our lives. My brother was one of the first classes to attend school in PS 234’s “new” building on Chambers street (a building it has now occupied for almost 30 years). By the time I was 16 years old, Stuyvesant High School had finished construction of the ten-story building it now occupies in Battery Park City at the corner of Chambers and West Streets, just in time for my Junior year. I was in English class in 1993 the day of the first bombing of the World Trade Center. And my family was at home on September 11th, 2001, as the planes struck the towers. For weeks afterward, my parents were confronted with checkpoints on their walk home from the subway, and the metallic smell of the fires lingered for what seemed like months. And, the gap left in the sky downtown was a cold reminder of a new reality — the quiet, peaceful village we had known was gone almost over night, and a creeping sense of unease settled in and stubbornly persisted.

Today, the neighborhood has grown exponentially, both becoming more populous and more affluent. Like the settlement of St. John’s Park in the 1820s, TriBeCa has once again become a destination for the city’s wealthiest and fashionable denizens, albeit on a far grander scale. And as a result, TriBeCa — including North TriBeCa — has become prime real-estate for developers looking to cash-in on the caché.

Uncovering the history of the neighborhood revealed that the changes taking place there are part of a continuum, part of the growth and regrowth of the city and our society as a whole. It also demonstrated that nothing takes place in a vacuum. Yet, seeking — and finding — the origins of this one particular spot, the land underneath my former home, also revealed a deeper truth.

Beneath the Surface

Hugh Gaine and the other property owners of the late 18th and early 19th century remade the waterfront to fulfill a vision of New York as an engine of maritime commerce and growing industrial power. Not content to abide within the natural boundaries of the island, they reshaped the geography of the land to accommodate their ambitious project, and pushed the river’s edge back from its high water mark further and further out into the effluvial channel. They forced nature to their will, forming and reforming the land to suit their needs.

In the two centuries that followed, the use of the waterfront reflected the changing character of the city, from pre-industrial port town, to bustling industrial city with steamships, railroads, warehouses and storage yards, to blighted metropolis whose derelict piers and empty commercial spaces would form the fertile, fallow ground in which a new city would emerge. The city of my lifetime transformed from an urban wilderness, where inhabiting the large swaths of post-industrial Manhattan was a new idea, to the settled Millennial city, tamer and taller, where the human-scale legacy of the industrial age was sloughed off and replaced with glass towers that loom high above the streets like lofty titans. Each successive wave of change built on and adapted to what the previous generation had left behind, shaping and reshaping the landscape to accommodate the social and economic forces at work in each period of history.

The destruction of the World Trade Center, and the economic crisis of 2008 slowed, but did not change the trajectory of transformation taking place in lower Manhattan. Where the builders of the 19th century and the city planners of the 1960s expanded the boundaries of the island horizontally, a new vision of the city is emerging, one in which the boundaries of the city are expanding vertically. Driven by the social and economic crucible that is 21st century America, and the forces at work in this more and more divided city, the relentless flow of energy that gives New York its strength is the same energy that strips it of lasting character and identity. Unable to preserve its past, the city cannibalizes itself, growing and regrowing to meet the needs of its population and the insatiable demands of capital.

The small strip of TriBeCa North that once was my home is no different; in a way, the drama that took place there over the course of two centuries is a perfect pageant play of the current moment in the history of New York City: the old giving way to the new, the human, artisanal scale of a place retreating before the impersonal bend of progress. In some ways tragic in the erasure of history and the physical forgetting of a city’s legacy; in other ways, simply another phase in a long journey of transformation.

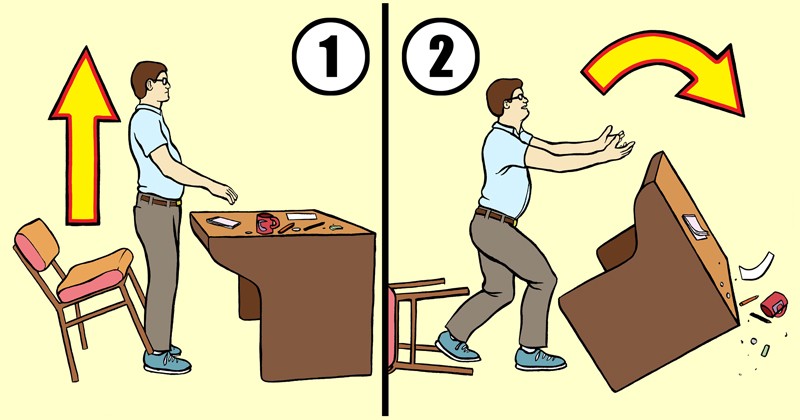

But there is another force at work that may represent a more pressing and urgent future than we are aware. The River itself — and the estuary where the Hudson meets the Atlantic Ocean — was the original claimant of the land, and may yet return to reclaim what was lost. If Hurricane Sandy prefigures things to come, the effects of climate change and rising sea levels will devastate and undo all of the development that has taken place around the Manhattan waterfront from before the time of Hugh Gaine. What once was water will return to water if no measures are put in place to safeguard the city from the relentless forces of nature.

Though perhaps that fate is all but unavoidable, and the four-odd centuries of urban development will be but a brief and fleeting moment in an enduring dance played out between the river and the sea.

More buildings in TriBeCa North are vulnerable to demolition. To learn more, and to support the effort to expand the Tribeca Historic District, visit the Tribeca Trust.

I am indebted to a number of individuals and organizations for their support in writing this article. The staff at the New York Public Library and their online archives, Lynn Ellsworth and the folks at the Tribeca Trust for their knowledge and research, the The New York City Department of Records and The Department of Buildings, The Landmarks Commission, The archives of the Museum of the City of New York, Welikia.org, the incredible resources available through Google Search, Google Maps, Google Earth, and Google Books, Ronnie, Jenny and Noah Landfield, and most of all, Caitlin and Benjamin for going with me the whole way.

Want more stories like this? Know some facts or details that I should know? Let me know what you think by leaving me a note!

Correction: A reader pointed out that the photo of Urban Renewal from 1965 shows the blocks north of Duane Street between West and Washington Streets, not North Moore street as previously stated.